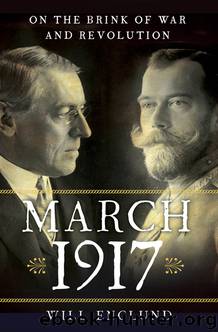

March 1917 by Will Englund

Author:Will Englund

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

CHAPTER 14

“The Great Liberal Leader of the World”

On Friday, March 16, Wilson finally got out of his sickbed and returned to work. “The President has had a bad cold and a sore throat,” an aide, Thomas W. Brahany, wrote in his diary. He was not seriously ill, Brahany wrote, yet the president’s doctor, Cary T. Grayson, had insisted he get complete bed rest. He had been out of circulation for ten days, though Edith had been reading him some of the long memoranda that the attorney general and secretary of state sent in to him. On the eleventh, when he was feeling a little better, he and his brother-in-law Randolph Bolling had taken out a Ouija board. Edith reported that none other than the specter of Lord Nelson, of Trafalgar fame, appeared, to talk about submarine warfare. (It isn’t clear what his opinion was.) But when William McAdoo, the secretary of the treasury who was also Wilson’s son-in-law, had paid a visit to him on the fourteenth, Wilson was visibly displeased, Brahany noted. McAdoo “stayed too long and talked too much.”

The White House barber told Brahany that after McAdoo left, Wilson erupted. “Dammit, he makes me tired. He’s got too much nerve. . . . I’m getting damn sick of it.”

But now the president was feeling better. He dispatched the mediators to New York to seek a settlement of the railroad dispute, and took care of other routine business. The next day, St. Patrick’s Day, Lansing sent him a long memo marked “Personal and Confidential” outlining the possibility that a peace settlement could be sought through dealings with Austria, Germany’s weak and crumbling ally and a country with which the United States had no argument. “It is my belief,” Lansing wrote, “that the Austrian Government is almost as fearful of its powerful ally as it is of its enemies.”

John Redmond, the Irish nationalist leader, sent sprigs of shamrock to all the White House staff, and the president put one into his lapel. The Irish posed a particularly thorny problem. It was just under a year since the Easter uprising in Dublin, which the British had ferociously put down, and ill will toward the English was still strong—and naturally strongest among the most vocal and committed Irish nationalists then in America. Irish-Americans held most of the political power in such Democratic strongholds as New York, Boston, Cleveland and Chicago. Liam Mellows, who led the Galway brigade in the Easter rebellion, was in Boston in March denouncing the English, arguing that they wanted the United States to join the war so that they could bring it back under British dominion. Theodore Roosevelt received a fascinating long letter at this time from a British officer who had been in Dublin the year before, recounting with evident pain the ways in which the British had completely mishandled the rising. It had had a significant effect on American opinion toward England. But Roosevelt wanted to ally with Britain, and he was continuously denouncing hyphenated Americans. A true American, he said, would love America more than he hated England.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12002)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4899)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4758)

The Templars by Dan Jones(4672)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4473)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4189)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3986)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3938)

Hitler in Los Angeles by Steven J. Ross(3935)

12 Strong by Doug Stanton(3539)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3317)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3180)

The Code Book by Simon Singh(3160)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3112)

The Art of War Visualized by Jessica Hagy(2986)

Hitler's Flying Saucers: A Guide to German Flying Discs of the Second World War by Stevens Henry(2739)

Babylon's Ark by Lawrence Anthony(2658)

The Second World Wars by Victor Davis Hanson(2510)

Tobruk by Peter Fitzsimons(2493)